This is the final article on the series I started so that we could celebrate the agile manifesto by re-investigating its twelve principles. And today it’s all about agile principle 12, the one that speaks of continuous improvement.

At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behavior accordingly.

If you’d rather watch a video than read, check out my Youtube video on Agile Principle #12:

Continuous improvement feels like something you hear a lot. But I wonder despite how much talk, what’s the percentage of it that is really absorbed or implemented?

You can ask yourself:

- How many opportunities for improvement are constantly catalogued, ranked, and experimented with in your team, in your department, in your organization?

- What gets shared about that with the whole organization?

- How are priorities for these improvement initiatives tackled?

- How is the ROI of these improvements measured, if at all, and then assessed against the hopes and dreams of whoever proposed the improvements?

If continuous improvement is a priority for your team or even your whole organization, then the agile principle 12 is a chapter that cannot be skipped.

Let’s dissect its elements.

Regular intervals

The notion of regular intervals is very interesting. You can and should learn at any given point in time when there’s a lesson to be learned. Immediately after an event. In a spur of the moment. A release just failed. The book launch did not achieve the numbers you expected. The beta app went viral (yes, you can also learn from success!).

But if you consider uneventful long stretches of time, you might be tempted to ignore the lessons behind all that normalcy. Your team might be doing something positive or more negative that ultimately is now compounding. So if you regularly inspect things you could potentially catch those before they snowball it into something bad. Or double down on what’s winning!

Also, consider that regular intervals create a cadence, a rhythm. That helps with making the learning habitual. It becomes part of what you do, a ritual, a habit. There’s a reason why people & companies do the quarterly and yearly reviews and roadmaps. Even nature checks-in with daily and seasonal rhythms.

That being the case, there’s opportunity for learning to become ingrained culturally and ritualistic in your team and organization. But while the ritual is necessary condition, it is not sufficient.

An important factor that ties to that is how much variation is allowed between team and company-wide cadences for learning. What could be beneficial in that? How can managers allow for that healthy variation? That’s the type of inquiry you, as an agile coach, could be exploring with your clients.

Think for your own reality: how do you already benefit from thinking at “regular intervals” in other moments of your life and work?

Time for reflections

If you need to reflect, you need at least two things: time and data.

That’s something you don’t necessarily find in a balanced ratio these days. How many teams and even just the individuals, stop and assess how things are doing in their busy-bee work schedules?

Stopping. Making time.

A lot of time, teams and managers alike complain that they don’t have enough time to deliver on things. The same people don’t stop, find time to assess if they are doing what is the most important thing and to see if they are going in the right direction. Say, the build breaks and people patch it and keep going never coming back and creating technical debt. That’s a long departure from the hopes of fixing problems at their root cause, not just the symptom.

Unsurprisingly, if they don’t “find the time” to execute better in the midst of execution, how can they find time for retrospectives!

It is not a luxury to stop and assess things. It is a business need. Mindless execution and continuous delivery of unwanted stuff is wasteful in time, in money and in opportunity, because it’s about creating pieces of products nobody asked for.

But another problem is also part of the equation of the agile principle 12, and I believe they add strongly to the reason why so many people tend to dislike sprint retrospectives.

Data. Without data, retrospectives are a chat about perception and feelings. Which are important, but they tell only part of the story. And not everybody wants to talk about their feelings all the time anyway, because feelings can be very disconnected from the facts. Data is what ground the discussion beyond ego, personal bias and it’s actually something that unites teams. Data also helps filter out the noise.

So, when the time comes for reflections, time is needed. And you need to be able to look, at least somewhat objectively at what happened. How efficient was the use of resources? What prevented you from reaching your desired outcome? Who was involved or should have been involved?

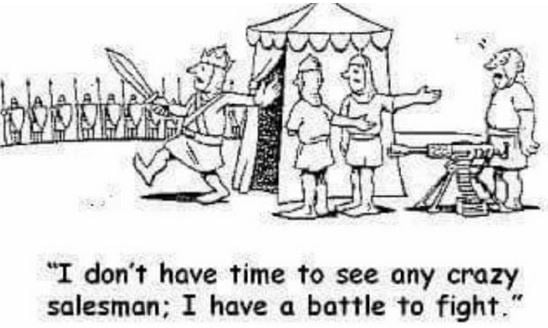

The matter of lack of time despite good intentions is so common that I bet you’ve seen those memes out there, showing how much faster, better and healthier you could execute, if only you “just had more time”.

Have you seen any of these pictures out there?

How could you be working with the leaders in your department or even the whole organization to start discussing what could it mean for them to start “making time”?

Tuning and adjusting

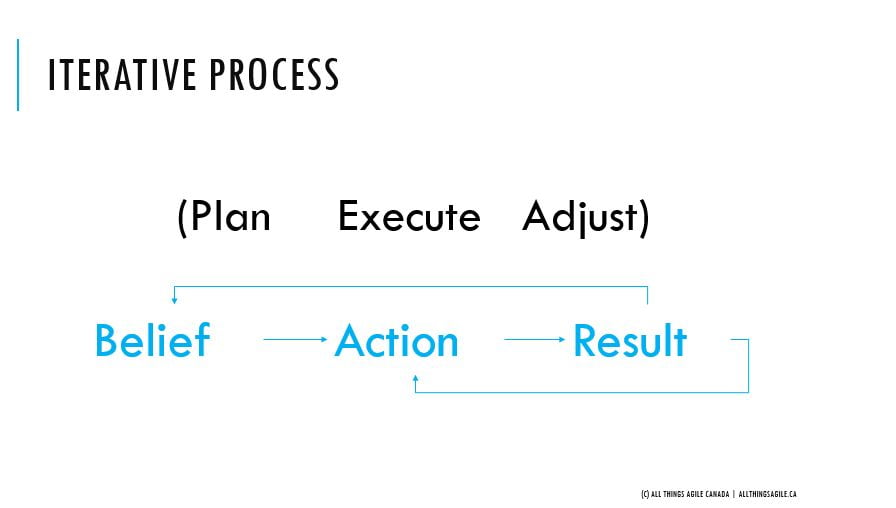

This is the true learning part of the agile principle 12: adjusting.

Learning is creating change. Learning s not when you just pick up a book and read. If nothing changed (how you think, how you act) you might have acquired information, but you did not learn.

The same for teams in organizations. Retrospectives and quarterly reviews happen. People look at whatever is presented. Things are discussed. But what will be done differently from now on?

It’s not a matter of thinking “Oh, I think this could have been different”. It’s about what you are committing to do moving forward because you believe in the positive correlation of certain actions versus certain results.

In the era of digital transformation, innovation is a sought-after trait. But innovation is misunderstood as some sort of inspiration or the muse. You hope to catch it. Yet, most innovative changes or those that bring big impact are products and ideas that come out of things that get done slightly differently. Or simply solving problems that people have been wanting to see solved for many years.

Take Uber Eats.

- So many people get takeout food in the Americas.

- So many restaurants also deliver in their nearby region.

- Some restaurants don’t.

What Uber did was just combine these 3 ideas. There is nothing new about any of them. But then UberEats went ahead and created an app and engaged with customers and partners in a different business model (you get paid from customers and restaurants).

What they did was to experiment. And to adjust. Regularly. They are now piloting delivering food via drones, but they surely did not start like that. They now are present worldwide, but surely they started locally actually right here in Canada, in Toronto, in 2015.

It all came to be as a result of a sequence of ordinary, slightly tweaked assumptions. That got tested. And people learned from it. That’s the agile principle 12 in action, even if you don’t want to talk about agile.

This is true for business, for processes and for people. While transformative ideas can appear from time to time, or we get that impression from the outside, it’s not uncommon that the sum of marginal gains is what truly transforms how people work and live their lives.

The product, the process, the learning

Continuous improvement is about everything in this triad: you learn about your product, about your process and about your own learning.

Inspecting and improving the product: what does it look like? Do people like it? Do people pay for it?

You see a lot of chat in social media and blog posts all about that customer satisfaction factor that everybody seems to want. And the product is a big piece of that. You know what else is needed?

Inspecting and improving the process. A product that everybody loves, but costs more than it brings in revenue is a failure. Your processes need to be effective and efficient. You can’t have a product that takes forever to be delivered, remember about satisfying the client through frequent deliveries? That requires changes in the process, in the way the product is made.

Finally, a big part of continuous improvement is change in how you think about your thinking. Are the assumptions used about the company values, the customer needs, the way things are, all just as valid as you thought they were? When change is really important, and to change company at a cultural level, it needs to expose and touch deeply into the ingrained thoughts.

That’s double loop learning.

While it’s unfortunate, it is also true so many organizations have nothing as such in place. Most of their learning is still superficial.

Final words

If you’ve been an agile coach, or at least an agile practitioner for quite some time, I think you can appreciate how much the agile principle 12 is at the heart of what agile, adaptive, ways mean. How many organizations get stuck in their current ways of thinking, while trying to adapt new ways of doing!

- Calling their 2 weeks “sprints”, but wanting all possible scope done.

- Wanting to create outcomes, while struggling to define value and prioritize what needs to be done.

- Hoping for the best delivery teams but creating role hierarchies that are not flexible enough.

- Wanting to be globally connected but forcing people to work in one uniform way no matter the culture of the country they are in.

Learning organizations have been a theme and a challenge for so many decades now. Agile has just put a spotlight on it. I found this interesting article form 1993 from the HBR saying how much the emphasis on experimenting is key. So, 30 years ago, people were already saying that. Even before an agile manifesto. And we say that, many more years after it too.

I believe that incorporating learning in ways of being is the final frontier for more adaptive organizations. When the agile coach comes in and shakes the structures, things take a new turn and excitement is generated. But eventually the coach will leave. So, you, as an agile coach, have a responsibility to early on start helping the organization to understand, conduct and own experimentation and commit to double-loop learning.

I hope this gets you excited!

How do you see yourself helping in that space?